9Īccording to Joseph Priestley, who almost certainly received his information directly from Franklin about fifteen years later, he did not perform the experiment himself at once because he believed a tower or spire would be needed to reach high enough to attract the electrical charge from a thunder cloud, and there was no structure in Philadelphia he deemed adequate for the purpose. This was the first public suggestion of an experiment to prove the identity of lightning and electricity. 8 He repeated the suggestion in July 1750 in his “Opinions and Conjectures,” with the important addition that a wire be run down from the rod to the ground or water, and he then proposed the “sentry-box” experiment. In the following March Franklin, writing to Collinson, suggested that pointed rods, instead of the usual round balls of wood or metal, be placed on the tops of weathervanes and masts, and that they would draw the electrical fire “out of a cloud silently,” thereby preserving buildings and ships from being struck by lightning. It was the pointed metal rod, with its peculiar effectiveness in electrical discharge, which both led to the suggestion and facilitated the experiment.

A test of lightning required the prior discoveries embodied in the “doctrine of points,” of which he was the undisputed author, and the knowledge he had gained of the role of grounding in electrical experiments.

Herein lies Franklin’s principal claim to priority in this great discovery. However obvious the suggestion of such an experiment may now seem, no one had made it before.

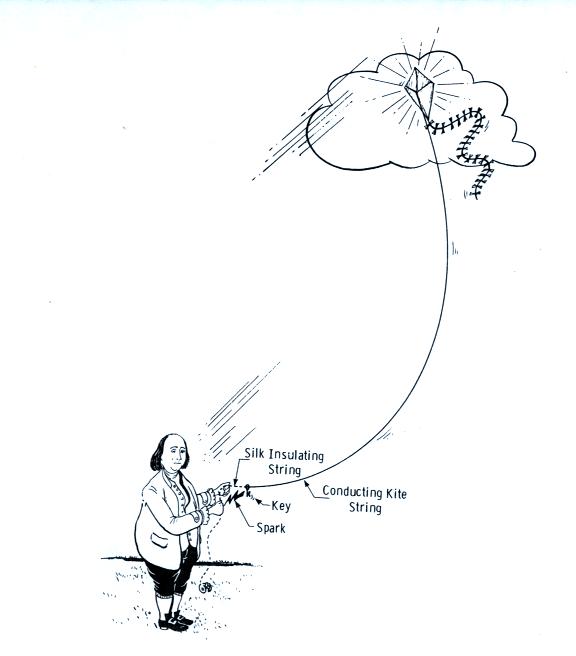

“But since they agree in all other particulars wherein we can already compare them, is it not probable they agree likewise in this? Let the experiment be made.” 7 6 In the “minutes” he kept of his experiments he listed under the date of November 7, 1749, twelve particulars in which “electrical fluid agrees with lightning,” and noted further that “the electrical fluid is attracted by points,” but that it was not yet known whether this property was also in lightning. 5 Franklin and his Philadelphia collaborators, working independently, also observed the similarities, and in his letter of April 29, 1749, to John Mitchell on thundergusts he took as the basis for his entire discussion the hypothesis that clouds are electrically charged. Franklin’s later adversary the Abbé Nollet wrote to the same effect in 1748. 4 For many years pioneer electricians had noted the similarity between electrical discharges and lightning, and in 1746 John Freke in England and Johann Heinrich Winkler in Germany separately advanced the idea of identity and suggested theories to account for it. This allowed him to stay on the ground and the kite was less likely to electrocute him.Franklin was the first scientist to propose that the identity of lightning and electricity could be proved experimentally, but he was not the first to suggest that identity, nor even the first to perform the experiment. Franklin realized the dangers of using conductive rods and instead used the conductivity of a wet hemp string attached to a kite.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)